A pathway for participation in research open source

James Howison, Jennifer Schopf

February 20, 2024

In planning for the University of Texas at Austin Open Source Program Office (UT-OSPO), funded by the Sloan Foundation in 2023, we worked to think about the impacts that we hoped to have on campus (and beyond).

In this effort, we were inspired by models of increasing engagement, sometimes broadly called “maturity models.” This approach helped bring together our OSPO team from across campus around the idea of a Participation Pathway.

- Using

- Researchers use appropriate open-sourceopen source software tools

- Contributing

- Research teams have a deeper understanding of an external software community, participate in identifying bugs, and askasking for new features

- Sharing

- Software from a team is made available using an open source license and on ana open platform facilitating collaboration (e.g., GitHub, GitLab, BitBucket, etc)

- Accepting

- An open source project receives contributions from outside the founding researchers

- Advancing Ecosystems (upstream/downstream)

- An open source project is part of a larger ecosystem of related projects with up and downstream dependencies

- Project members contribute and mentor in upstream and downstream projects

In this blog post we discuss maturity models and present the UT OSPO Participation Pathway illustrated with case study examples from the NetSage open source project.

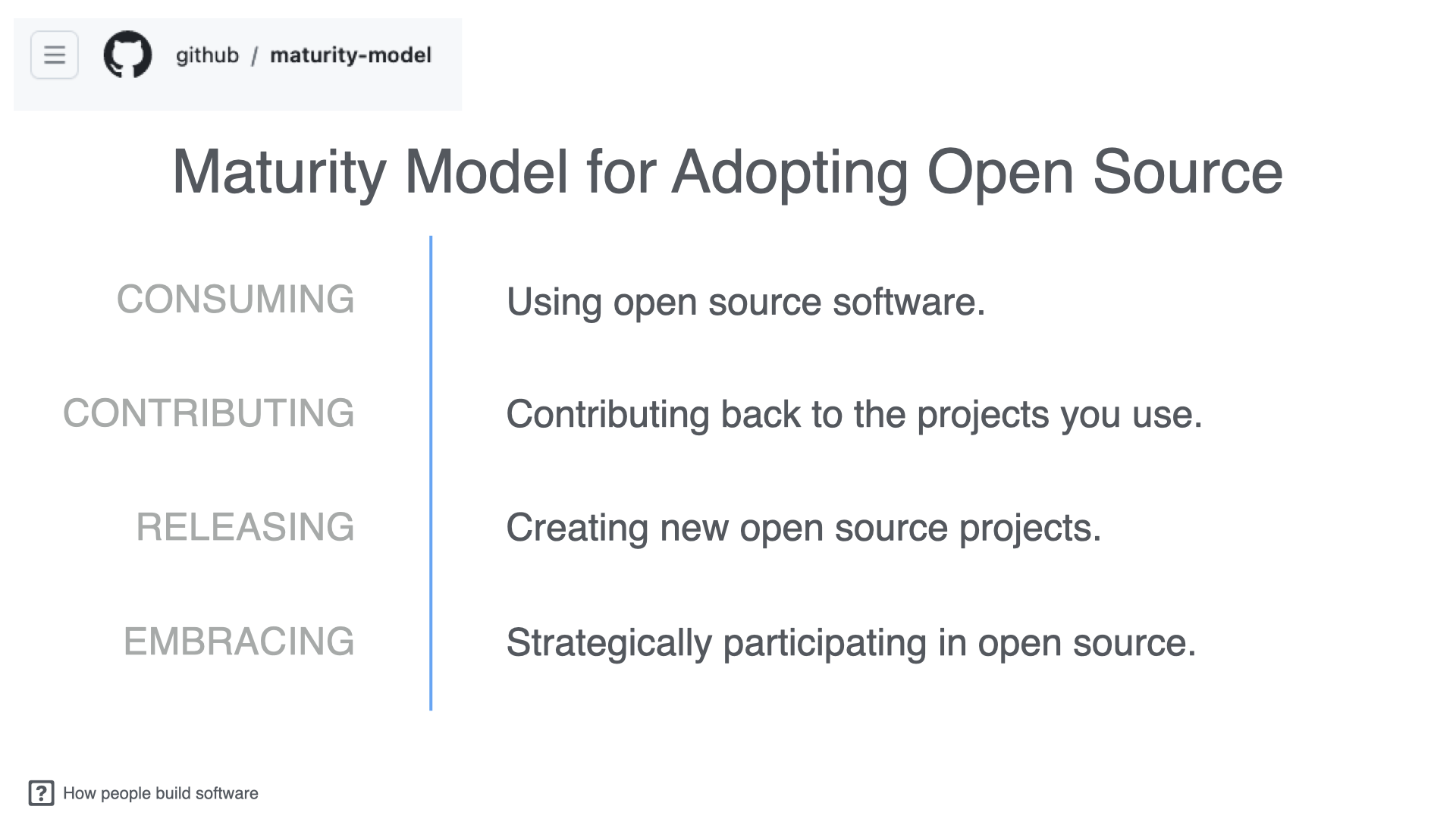

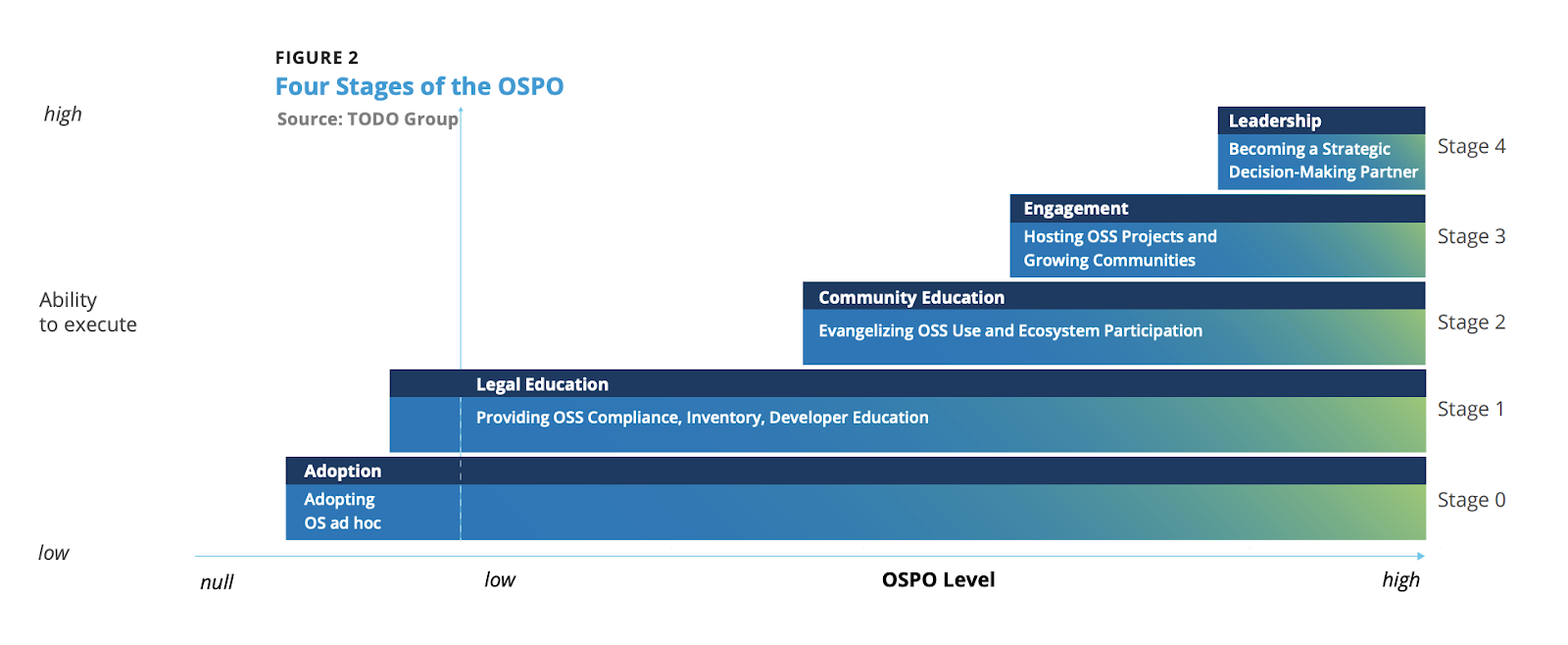

Maturity models that inspired us

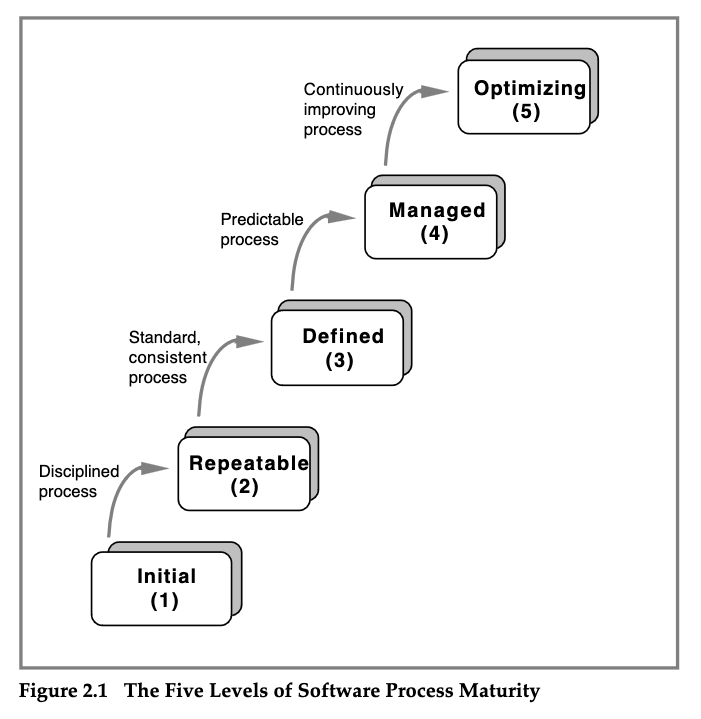

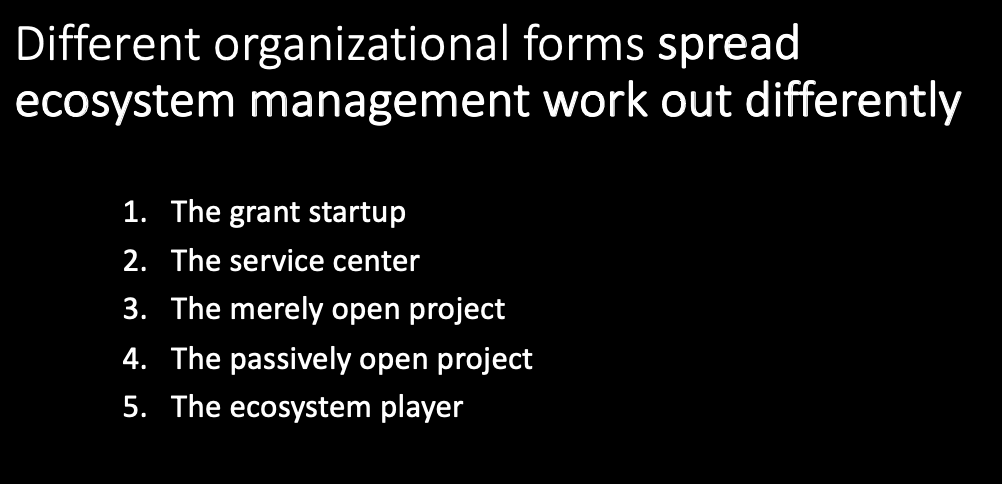

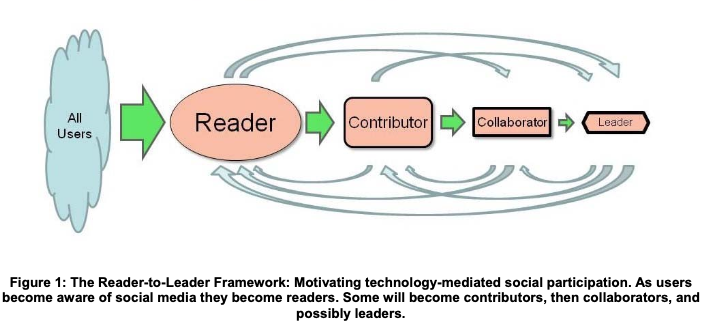

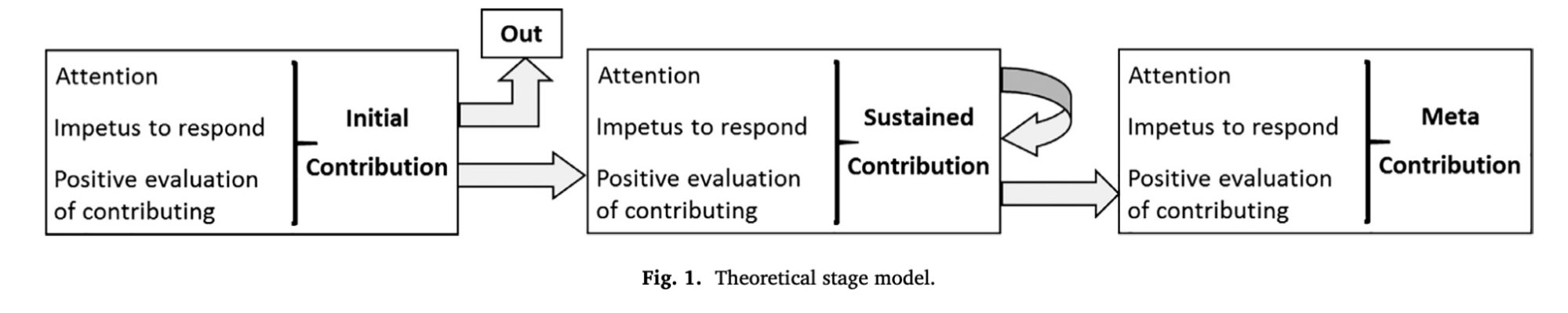

Maturity models for open source practice describe activities observed around open source and research, and are generally arranged in a progression that is part biographical description of a participant’s journey and part an abstraction of how improving practices benefit the overall world of open collaboration.

At the earlier/lower levels in these models, we find many people, with decreasing numbers at later/higher levels: almost everyone can and should progress from earlier/lower levels, but fewer people are needed at the higher levels of participation (with their activities having magnified impact).

We found these sorts of models helped us in two ways. First, they helped us conceive a developmental process with transitions between activities that we could help foster (and potentially measure). Second, the models helped us think about the number of researchers across campus that our OSPO could reach, and thus identify the transitions between levels in which we could have the greatest beneficial impact.

Our team brings together stakeholders from across the university:

- those building and supporting open source tools used in research,

- an organization scientist who has studied research software development,

- librarians who work with researchers around data and field-specific computing,

- supercomputing center leadership from Texas Advanced Computing Center (TACC)

- leaders in university and research IT, and

- development officers experienced in improving research communication.

Together we simplified and developed the model shown in Figure 1, which helped us coalesce and understand each other’s perspectives and imagine our activities in an integrated way. Initially we call this a “capability maturity model” but eventually settled on a “pathway to participation.”

We considered including a “Level 0” which is sometimes used to describe existing poor practices that are the target of intended change. We considered the absence of the use of software, but we decided that it was likely rare and too deep within the specifics of individual research fields. We also considered a distinction between visible and invisible use, or each of the Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, or Reusable principles in FAIR4RS (Chue Hong et al., 2021). Ultimately, though, we decided that while these practices of openness are desirable, they aren’t clearly a precursor to useful participation in open software ecosystems. Good individual/team software development practices can evolve at the same time with useful participation in research-oriented open communities.

We also considered a “Level 6” (Stewardship) involving planning and influence on the structure or dynamics of packages and dependencies in nearby package and data flow ecosystems, and obtaining resources to improve ecosystems (e.g., inviting mentors, advising funding bodies, mentoring grant applications, encouraging industry participation). We decided this was out of scope for our OSPO, at least at present.

NetSage participation pathway case study

The history of the NetSage (http://netsage.io, NSF#1540933, #1826994, #2328479) project shows how a participation pathway can work in practice. NetSage started ten years ago as a measurement and monitoring tool to understand the movement of large data flows between endpoints. It is currently deployed by dozens of research and education networks worldwide and had over 4,000 unique visitors to its supported dashboards in 2022.

From the beginning, NetSage leveraged other open-source tools to gather network data, such as perfSONAR, and open protocols, such as SMNP. In this way, it Used open-source tools. The initial database was the open-source Time Series Data Base (TSDS https://github.com/GlobalNOC/tsds-services). The initial framework that gathered and displayed the data was written from scratch by the team. The code was archived in GitHub with an open-source license, but no one except the funded project team ever touched that archive or tried to deploy the software directly; the project had not yet moved along the participation pathway to Accepting.

In the process of using these data collection tools, the NetSage team contributed back to these offerings by identifying bugs and needed features, and at times worked closely with the developers to work through edge cases that the NetSage infrastructure would find, enacting the idea of Pushing downstream.

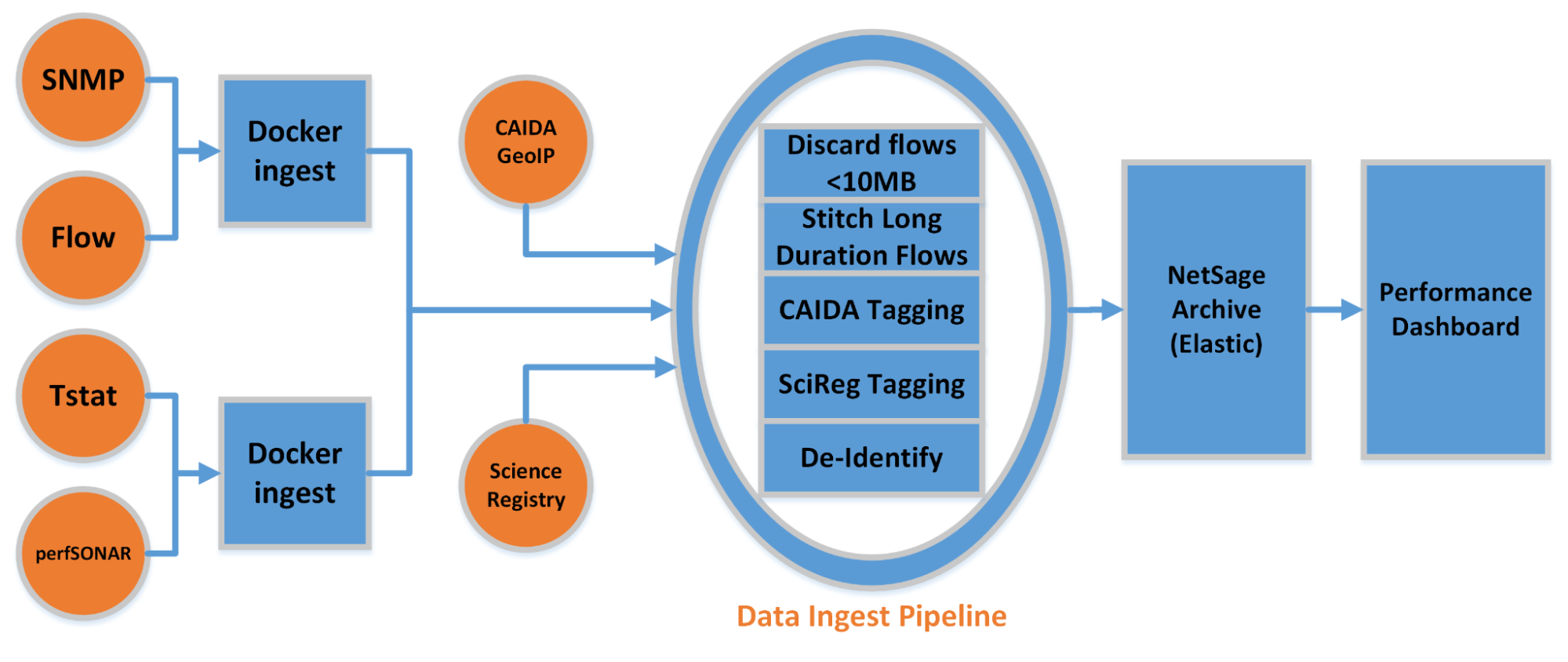

In its third year, the decision was made to shift from a bespoke internal framework to the use of the open-source tool Grafana to display its data, in part because it could work with multiple backend databases. By this time, the project was looking at collecting flow data from routers, using open protocols such as NetFlow. This data was then deposited in an Elastic database, furthering the project’s use of open-source tools. At this point, the architecture shown in Figure 2 was used for the project. The core software, stitching together contributions from various open-source communities, was released and licensed.

In Year 6, the Energy Science Network (ESnet) decided to rebuild its monitoring and measurement infrastructure and created StarDust, a variant of NetSage. It used much of the NetSage code, but added in different information sources, such as the way that ESnet collected SNMP data. This module was accepted into the NetSage codebase and later used by the TACC/EPOC NetSage deployments.

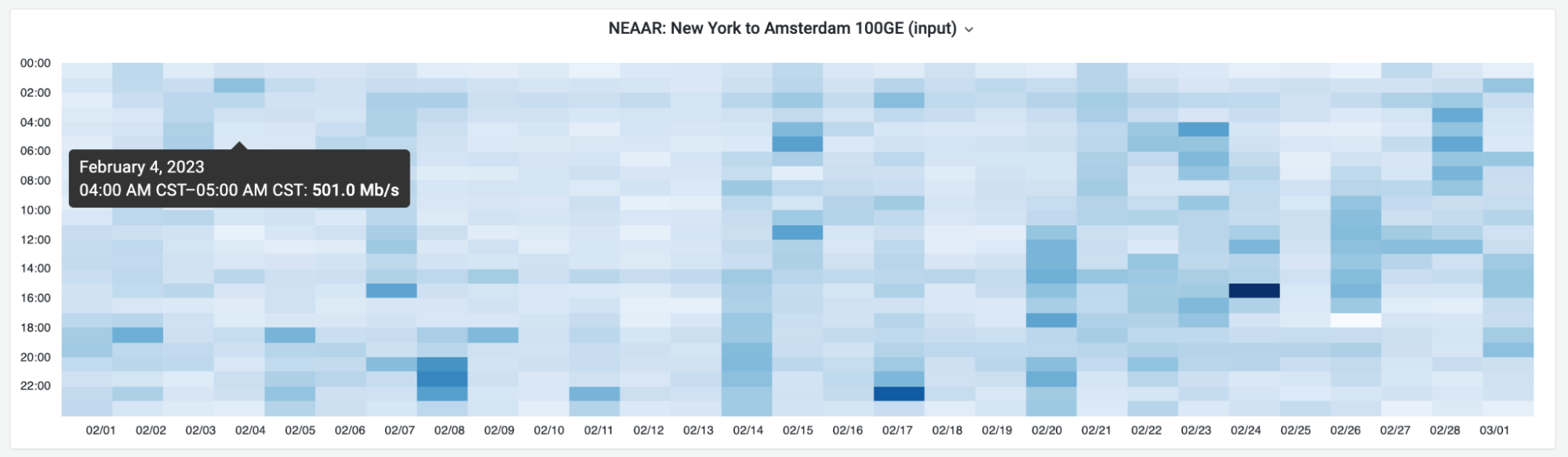

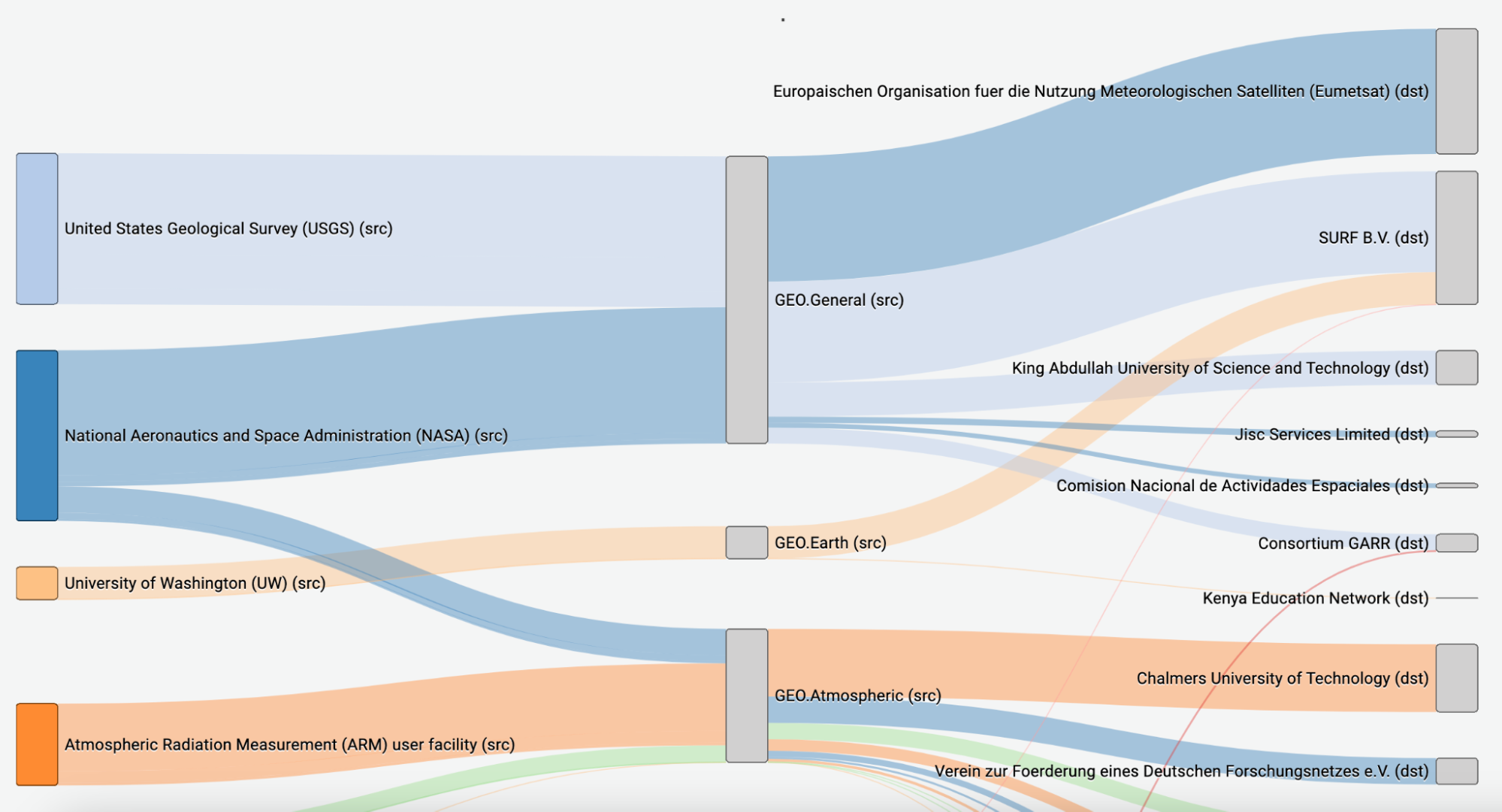

In addition, as the project matured, NetSage developers created additional ways to collect or display data. These included displays for Heatmaps (Figure 3), Sankey Graphs (Figure 4), and Slope Graph (Figure 5). We developed these because we needed them, yet graphics are only tangentially related to the core functionality of NetSage. We also thought that these might be useful to a broader community (and that their future maintenance would be easier there). These plugins were then contributed back to the Grafana open-source project (pushed upstream), thereby advancing the larger ecosystem of tools available to the broader community. Grafana has more than 20 million users.

Conclusion

The participation pathway, derived from maturity models, helps the UT-OSPO conceptualize the impact we plan to have. The NetSage case study, above, shows how the framework helps rethink through the history of a mature project to see elements of the pathway unfold. As is clear in the case study, while the pathway has a biographical or logical flow that helps build a shared understanding of activity, we don’t mean that the pathway will necessarily be linear!

In addition to working with projects like NetSage already releasing code for the use of others, the UT-OSPO also plans to work with people across campus that aren’t releasing code for others to use. For example, we plan to work with research groups to help their internal practices to align better with open and reproducible science, from using source code control, employing build systems and containerization (for reproducibility and software release). We also plan to work with people (especially students and postdocs) interacting with open-source projects, including mentoring early participation from issue discussions, feature requests, and initial contributions.

We hope the participation pathway can be useful for others in helping disparate groups unite on a vision for working together. Overall, we hope to facilitate improved software practices that increasingly align with open-source ecosystems, enhancing the impact of the software work done in the university’s research mission.

We look forward to working with other OSPOs, in universities and in industry, and in participating in the OSPO++ community and OSPO networks like CURIOSS.

You can get in touch via the contact details at our website: https://opensource.utexas.edu/

References

References

Chue Hong, N. P., Katz, D. S., Barker, M., Lamprecht, A.-L., Martinez, C., Psomopoulos, F. E., Harrow, J., Castro, L. J., Gruenpeter, M., Martinez, P. A., & Honeyman, T. (2021, June 10). FAIR Principles for Research Software (FAIR4RS Principles). RDA. https://www.rd-alliance.org/group/fair-research-software-fair4rs-wg/outcomes/fair-principles-research-software-fair4rs Crowston, K., & Fagnot, I. (2018). Stages of motivation for contributing user-generated content: A theory and empirical test. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 109, 89–101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijhcs.2017.08.005 GitHub. (2016, January 13). A maturity model for embracing open source. https://github.com/github/maturity-model Howison, J. (2021, January 14). CISE Distinguished Lecture: Software Sustainability, Routes to Peer Production, Ecosystem Complexity. [Presentation]. figshare. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.13574870.v1 Paulk, M. C., Curtis, B., Chrissis, M. B., & Weber, C. V. (1993). Capability Maturity Model for Software, Version 1.1: Defense Technical Information Center. https://doi.org/10.21236/ADA263403 Preece, J., & Shneiderman, B. (2009). The Reader-to-Leader Framework: Motivating Technology-Mediated Social Participation. AIS Transactions on Human-Computer Interaction, 1(1), 13–32. TODO Group. (2023). OSPO Landscape. OSPO Landscape. https://landscape.todogroup.org